Johann Sebastian Bach[a] (31 March [O.S. 21 March] 1685 – 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the Baroque period. He is known for instrumental compositions such as the Brandenburg Concertos and the Goldberg Variations as well as for vocal music such as the St Matthew Passion and the Mass in B minor. Since the 19th-century Bach Revival he has been generally regarded as one of the greatest composers of all time.[3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Sebastian_Bach

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Sebastian_Bach

Passions and oratorios

Bach composed Passions for Good Friday services and oratorios such as the Christmas Oratorio, which is a set of six cantatas for use in the liturgical season of Christmas.[128][129][130] Shorter oratorios are the Easter Oratorio and the Ascension Oratorio.

St Matthew Passion

With its double choir and orchestra, the St Matthew Passion is one of Bach's most extended works.

St John Passion

The St John Passion was the first Passion Bach composed during his tenure as Thomaskantor in Leipzig.

Cantatas

According to his obituary, Bach would have composed five-year cycles of sacred cantatas, and additional church cantatas for instance for weddings and funerals.[94] Approximately 200 of these sacred works are extant, an estimated two thirds of the total number of church cantatas he composed.[4][131] The Bach Digital website lists 50 known secular cantatas by the composer,[132]about half of which are extant or largely reconstructable.[133]

Church cantatas

Bach's cantatas vary greatly in form and instrumentation, including those for solo singers, single choruses, small instrumental groups, and grand orchestras. Many consist of a large opening chorus followed by one or more recitative-aria pairs for soloists (or duets) and a concluding chorale. The melody of the concluding chorale often appears as a cantus firmus in the opening movement.

Bach's earliest cantatas date from his years in Arnstadt and Mühlhausen. The earliest one with a known date is Christ lag in Todes Banden, BWV 4, for Easter 1707, which is one of his chorale cantatas.[134] Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit, BWV 106, a.k.a. Actus Tragicus, is a funeral cantata from the Mühlhausen period.[135] Around 20 church cantatas are extant from his later years in Weimar, for instance, Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, BWV 21.[136]

After taking up his office as Thomaskantor late May 1723, Bach performed a cantata each Sunday and feast day that corresponded to the lectionary readings of the week.[17] His first cantata cycle ran from the first Sunday after Trinity of 1723 to Trinity Sunday the next year. For instance, the Visitation cantata Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben, BWV 147, containing the chorale that is known in English as "Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring", belongs to this first cycle. The cantata cycle of his second year in Leipzig is called the chorale cantata cycle as it is mainly consisting of works in the chorale cantata format. His third cantata cycle was developed over a period of several years, followed by the Picander cycle of 1728–29.

Later church cantatas include the chorale cantatas Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 80 (final version)[137] and Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140.[138] Only the first three Leipzig cycles are more or less completely extant. Apart from his own work, Bach also performed cantatas by Telemann and by his distant relative Johann Ludwig Bach.[17]

Secular cantatas

Bach also wrote secular cantatas, for instance for members of the Royal-Polish and Prince-electoral Saxonian family (e.g. Trauer-Ode),[139] or other public or private occasions (e.g. Hunting Cantata).[140] The text of these cantatas was occasionally in dialect (e.g. Peasant Cantata)[141] or in Italian (e.g. Amore traditore).[142] Many of the secular cantatas went lost, but for some of these the text and the occasion are known, for instance when Picander later published their libretto (e.g. BWV Anh. 11–12).[143]Some of the secular cantatas had a plot carried by mythological figures of Greek antiquity (e.g. Der Streit zwischen Phoebus und Pan),[144] others were almost miniature buffo operas (e.g. Coffee Cantata).[145]

A cappella music

Bach's a cappella music includes motets and chorale harmonisations.

Motets

Bach's motets (BWV 225–231) are pieces on sacred themes for choir and continuo, with instruments playing colla parte. Several of them were composed for funerals.[146] The six motets certainly composed by Bach are Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied, Der Geist hilft unser Schwachheit auf, Jesu, meine Freude, Fürchte dich nicht, Komm, Jesu, komm, and Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden. The motet Sei Lob und Preis mit Ehren (BWV 231) is part of the composite motet Jauchzet dem Herrn, alle Welt (BWV Anh. 160), other parts of which may be based on work by Telemann.[147]

Chorale harmonisations

Bach wrote hundreds of four-part harmonisations of Lutheran chorales.

Church music in Latin

Bach church music in Latin includes his Magnificat, four Kyrie–Gloria Masses, and his Mass in B minor.

Magnificat

The first version of Bach's Magnificat dates from 1723, but the work is best known in its D major version of 1733.

Mass in B minor

In 1733 Bach composed a Kyrie–Gloria Mass for the Dresden court. Near the end of his life, around 1748–1749 he expanded this composition into the large-scale Mass in B minor. The work was never performed in full during Bach's lifetime.[148][149]

Keyboard music

Bach wrote for the organ and other keyboard instruments of his day, mainly the harpsichord, but also the clavichord and his personal favourite: the lute-harpsichord (the compositions listed as works for the lute, BWV 995-1000 and 1006a were probably written for this instrument).

Organ works

Bach was best known during his lifetime as an organist, organ consultant, and composer of organ works in both the traditional German free genres—such as preludes, fantasias, and toccatas—and stricter forms, such as chorale preludes and fugues.[17] At a young age, he established a reputation for his great creativity and ability to integrate foreign styles into his organ works. A decidedly North German influence was exerted by Georg Böhm, with whom Bach came into contact in Lüneburg, and Dieterich Buxtehude, whom the young organist visited in Lübeck in 1704 on an extended leave of absence from his job in Arnstadt. Around this time, Bach copied the works of numerous French and Italian composers to gain insights into their compositional languages, and later arranged violin concertos by Vivaldi and others for organ and harpsichord. During his most productive period (1708–1714) he composed about a dozen pairs of preludes and fugues, five toccatas and fugues, and the Little Organ Book, an unfinished collection of forty-six short chorale preludes that demonstrates compositional techniques in the setting of chorale tunes. After leaving Weimar, Bach wrote less for organ, although some of his best-known works (the six trio sonatas, the German Organ Mass in Clavier-Übung III from 1739, and the Great Eighteen chorales, revised late in his life) were composed after his leaving Weimar. Bach was extensively engaged later in his life in consulting on organ projects, testing newly built organs, and dedicating organs in afternoon recitals.[150][151] The Canonic Variations on "Vom Himmel hoch da komm' ich her"and the Schübler Chorales are organ works Bach published in the last years of his life.

Harpsichord and clavichord

Bach wrote many works for harpsichord, some of which may have been played on the clavichord. The larger works are usually intended for a harpsichord with two manuals, while performing them on a keyboard instrument with a single manual (like a piano) may provide technical difficulties for the crossing of hands. Many of his keyboard works are anthologies that encompass whole theoretical systems in an encyclopaedic fashion.

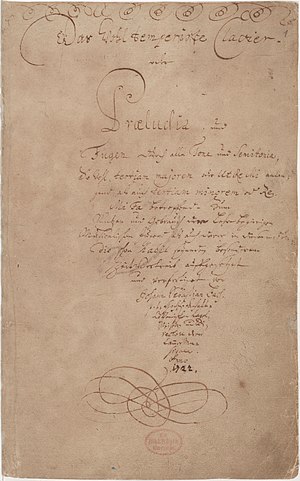

- The Well-Tempered Clavier, Books 1 and 2 (BWV 846–893). Each book consists of a prelude and fugue in each of the 24 major and minor keys in chromatic order from C major to B minor (thus, the whole collection is often referred to as "the 48"). "Well-tempered" in the title refers to the temperament (system of tuning); many temperaments before Bach's time were not flexible enough to allow compositions to utilise more than just a few keys.[152][153]

- The Inventions and Sinfonias (BWV 772–801). These short two- and three-part contrapuntal works are arranged in the same chromatic order as The Well-Tempered Clavier, omitting some of the rarer keys. These pieces were intended by Bach for instructional purposes.[154]

- Three collections of dance suites: the English Suites (BWV 806–811), the French Suites (BWV 812–817), and the Partitas for keyboard (Clavier-Übung I, BWV 825–830). Each collection contains six suites built on the standard model (Allemande–Courante–Sarabande–(optional movement)–Gigue). The English Suites closely follow the traditional model, adding a prelude before the allemande and including a single movement between the sarabande and the gigue.[155] The French Suites omit preludes, but have multiple movements between the sarabande and the gigue.[156] The partitas expand the model further with elaborate introductory movements and miscellaneous movements between the basic elements of the model.[157]

- The Goldberg Variations (BWV 988), an aria with thirty variations. The collection has a complex and unconventional structure: the variations build on the bass line of the aria, rather than its melody, and musical canons are interpolated according to a grand plan. There are nine canons within the thirty variations; every third variation is a canon.[158] These variations move in order from canon at the unison to canon at the ninth. The first eight are in pairs (unison and octave, second and seventh, third and sixth, fourth and fifth). The ninth canon stands on its own due to compositional dissimilarities. The final variation, instead of being the expected canon at the tenth, is a quodlibet.

- Miscellaneous pieces such as the Overture in the French Style (French Overture, BWV 831) and the Italian Concerto (BWV 971) (published together as Clavier-Übung II), and the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue (BWV 903).

Among Bach's lesser known keyboard works are seven toccatas (BWV 910–916), four duets (BWV 802–805), sonatas for keyboard (BWV 963–967), the Six Little Preludes (BWV 933–938), and the Aria variata alla maniera italiana (BWV 989).

Orchestral and chamber music

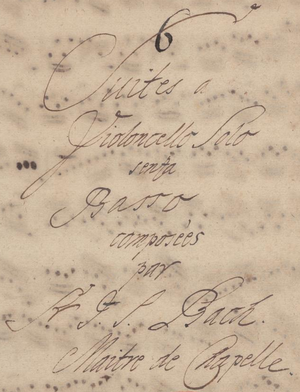

Bach wrote for single instruments, duets, and small ensembles. Many of his solo works, such as his six sonatas and partitas for violin (BWV 1001–1006) and his six cello suites (BWV 1007–1012), are widely considered among the most profound in the repertoire.[159] He wrote sonatas for a solo instrument such as the viola de gamba accompanied by harpsichord or continuo, as well as trio sonatas (two instruments and continuo).

The Musical Offering and The Art of Fugue are late contrapuntal works containing pieces for unspecified (combinations of) instruments.

Violin concertos

Surviving works in the concerto form include two violin concertos (BWV 1041 in A minor and BWV 1042 in E major) and a concerto for two violins in D minor, BWV 1043, often referred to as Bach's "double" concerto.

Brandenburg Concertos

Bach's best-known orchestral works are the Brandenburg Concertos, so named because he submitted them in the hope of gaining employment from Margrave Christian Ludwig of Brandenburg-Schwedt in 1721; his application was unsuccessful.[17] These works are examples of the concerto grosso genre.

Keyboard concertos

Bach composed and transcribed concertos for one to four harpsichords. Many of the harpsichord concertos were not original works, but arrangements of his concertos for other instruments now lost.[160] A number of violin, oboe, and flute concertos have been reconstructed from these.

Orchestral suites

In addition to concertos, Bach wrote four orchestral suites, each suite being a series of stylised dances for orchestra, preceded by a French overture.[161]

Copies, arrangements and works with an uncertain attribution

In his early youth, Bach copied pieces by other composers to learn from them.[162] Later, he copied and arranged music for performance and/or as study material for his pupils. Some of these pieces, like "Bist du bei mir" (not even copied by Bach but by Anna Magdalena), became famous before being dissociated with Bach. Bach copied and arranged Italian masters such as Vivaldi (e.g. BWV 1065), Pergolesi (BWV 1083) and Palestrina (Missa Sine nomine), French masters such as François Couperin (BWV Anh. 183), and closer to home various German masters, including Telemann (e.g. BWV 824=TWV 32:14) and Handel (arias from Brockes Passion), and music from members of his own family. Then he also often copied and arranged his own music (e.g. movements from cantatas for his short masses BWV 233–236), as likewise his music was copied and arranged by others. Some of these arrangements, like the late 19th-century "Air on the G String", helped in popularising Bach's music.

Sometimes who copied whom is not clear. For instance, Forkel mentions a Mass for double chorus among the works composed by Bach. The work was published and performed in the early 19th century, and although a score partially in Bach's handwriting exists, the work was later considered spurious.[163] In 1950, the setup of the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis was to keep such works out of the main catalogue: if there was a strong association with Bach they could be listed in its appendix (in German: Anhang, abbreviated as Anh.), so, for instance, the aforementioned Mass for double chorus became BWV Anh. 167. This was however far from the end of attribution issues—for instance, Schlage doch, gewünschte Stunde, BWV 53 was later re-attributed to Melchior Hoffmann. For other works, Bach's authorship was put in doubt without a generally accepted answer to the question whether or not he composed it: the best known organ composition in the BWV catalogue, the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565, was indicated as one of these uncertain works in the late 20th century.[164]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_compositions_by_Johann_Sebastian_BachCompositions

|

Cantata Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140 performed by the MIT Concert Choir conducted by W. Cutter

|

|

from Mass in B minor

|

|

Prelude and Fugue in A minor, BWV 543 performed by Noah Horn on the 1974 Dirk A. Flentrop organ at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music

|

|

Italian Concerto BWV 971 performed by Martha Goldstein

|

|

|

|

Some of Bach's most popular melodies are, more often than not, heard in various arrangements:

"Air", 2nd movement from Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D major, BWV 1068, performed in a Air on the G Stringadaptation by Capella Istropolitanaconducted by Oliver von Dohnányi(courtesy of Naxos)

The Aria "Schafe können sicher weiden" (Sheep May Safely Graze), No. 9 from the Hunting Cantata, BWV 208: composed for soprano, recorders and continuo the music of this movement exists in a variety of instrumental arrangements.

|

In 1950, Wolfgang Schmieder published a thematic catalogue of Bach's compositions, called Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (Bach Works Catalogue).[123] Schmieder largely followed the Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe, a comprehensive edition of the composer's works that was produced between 1850 and 1900. The first edition of the catalogue listed 1,080 surviving compositions without doubt composed by Bach.[124]

| BWV Range | Compositions |

|---|---|

| BWV 1–224 | Cantatas |

| BWV 225–231 | Motets |

| BWV 232–243 | Liturgical compositions in Latin |

| BWV 244–249 | Passions and Oratorios |

| BWV 250–438 | Four-part chorales |

| BWV 439–524 | Small vocal works |

| BWV 525–771 | Organ compositions |

| BWV 772–994 | Other keyboard works |

| BWV 995–1000 | Lute compositions |

| BWV 1001–1040 | Other chamber music |

| BWV 1041–1071 | Orchestral music |

| BWV 1072–1078 | Canons |

| BWV 1079–1080 | Late contrapuntal works |

BWV 1081–1126 were added to the catalogue in the second half of the 20th century, and BWV 1127 and higher were still later additions.[125][126][127]

No comments:

Post a Comment